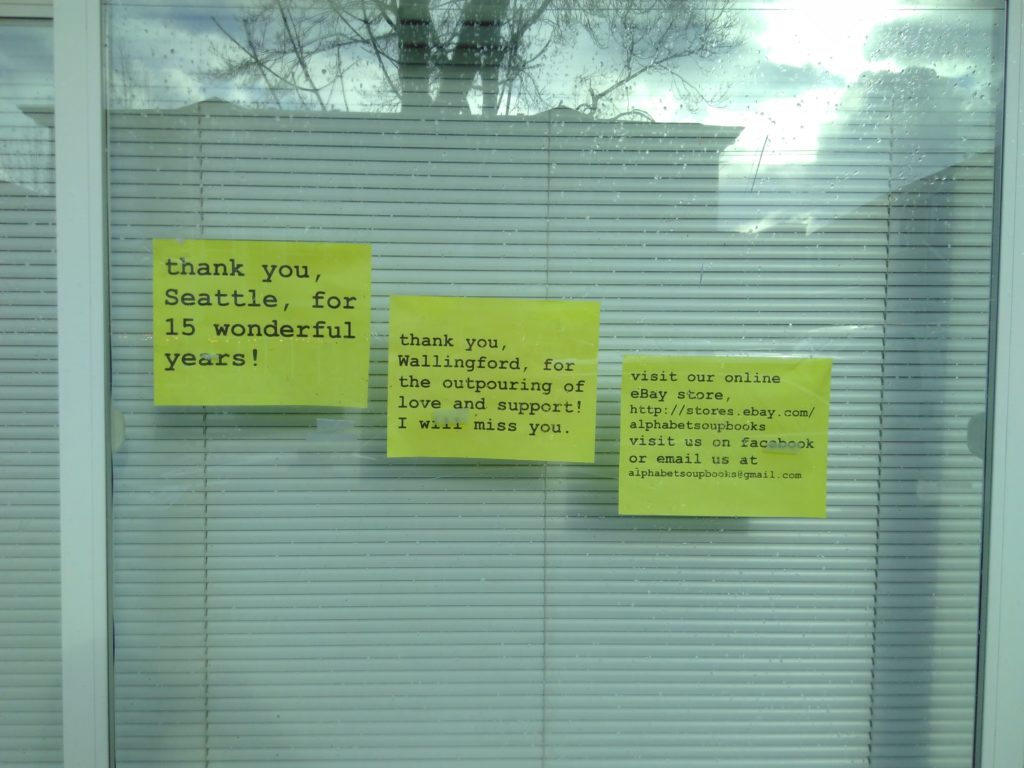

As I am walking the streets of Seattle, I see shops closing down. Recently I came across the cute little bookstore Alphabet Soup. Wallingford said goodbye – after 15 years.

A little bit further down the same road, I passed a place that used to be a theatre and an adjoining café. There has been a time that wonderful plays were performed here. The audience cheered at the end. People spoke about the performance for hours, with a drink next door. Look at it now. It is no longer. Also the buildings themselves lost all their glory.

Many people experience sadness, looking at the end of things like this. In some ways that is understandable. Think for example about those who lost their income. Yet, it also reveals a truth about reality: everything is impermanent. Which, according to buddhist tradition, is something to celebrate. Why? How can we look at impermanence with joy? Furthermore, what are the implications for our daily lives?

To answer these questions we need at least three things. First of all, a first description of ‘impermanence’. Secondly, a fresh mind to examine this. Thirdly, as Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche says in his wonderful book Rebel Buddha:

“We all want to find some meaningful truth about who we are,” Ponlop Rinpoche writes, “but we can only find it guided by our own wisdom – by our own rebel buddha within.”

How can we unleash this rebel buddha to deepen our practical understanding of buddhist teachings, like those about impermanence?

Understanding the concept ‘impermanence’ does not seem to be very difficult. Everything that appears to us – the theatre-building, the furniture, the stage and so on – will eventually fall apart. Perhaps a fundraiser could have kept it open for a few more years. Some theatres, on Broadway in New York City for example, might last longer than this relatively small one in Wallingford, Seattle. But sooner or later, they will all come to an end.

This is a little bit easier to grasp considering the things happening in the theatre. The play and the evening we enjoyed so much does not last for ever. No matter how much we want it to. ‘Impermanence’ simply refers to the fact that everything is subject to change, decline, and finally destruction. We could also say, things come, pass and go again.

The difficulty for many is not such much realizing that ’things’ are impermanent. Even that evenings at the theatre come to an end, after one last drink. However, what goes for these ’things’, is also true for our thoughts, emotions and – even – our ‘self’. I remember how the first time I heard about this from a buddhist teacher I felt a bit unease. I was not really sure whether I was happy where his teaching was going. I have noticed other people experience something similar. Even to a point where some say they directly feel depressed.

Soon, however, after critically examining it, I realised it to be true as well: thoughts and emotions do not last either. Moreover, but this took me a lot more time to see, it is actually pointing to a road of joy and freedom.

Let’s think for a moment about ourselves as actors on the stage of life, a metaphor brought forward by Shakespeare. Imagine you would need to play the same scene, as the same character, over and over again. For the same people. In the same place. Would that not be exhausting and depressing? How wonderful would it be if, every day, we can choose to be a new character, live a new story, play for a new audience. Suddenly there is a lot of freedom, isn’t there? Once we realize this, we can sense the openness, a space that allows for creativity and playfulness.

Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche uses another metaphor to explain this. He speaks about a prison. Not a prison in the ordinary sense, with walls and prisoners who are locked inside. But a prison of our so-called conceptual world. We have constructed a story about the world as if it is solid. Yet, this is an illusion. Not the reality. Rinpoche refers to the words of the Buddha who taught that what lies at the heart of our suffering – this feeling of heaviness we can have – is not knowing the reality of things. Whereas our natural state is freedom. Seeing that all things, including ourselves, ‘material’ and ‘mental’, are impermanent helps us to recognize that and start to live our potential of joy and happiness fully.

Knowing this, we can still go to the theatres and enjoy new plays. There is nothing ‘wrong’ with that. Plays can be inspiring. Make us contemplate about life. Touch our heart. I experienced this when I visited Lazarus – the musical written by the great performer David Bowie before he passed away.

Recollecting that experience makes me think: Dzogchen Ponlop Rinpoche might be very much like David Bowie. Both point the world as a bit of a strange place in which humans get caught up in harmful views, fear and unhappiness. Both say there is a rebel within us that can and wants to break free. Bowie called that maybe Blackstar. Whereas Rinpoche calls it our own awakened mind. The point is, we can unleash this rebel within us, free ourselves from suffering, and live a meaningful live in freedom. Are you ready to play joyfully in the never-closed theatre of impermanence?

(This article is originally written for Nalandabodhi Seattle / NalandaWest and the introduction of Fresh Minds / discussion of Rebel Buddha. Check here for more information: seattle.nalandabodhi.org / nalandawest.org.)